I am supporting Robert F. Kennedy Jr. in his independent / new party campaign for president, despite having disagreements with him on some issues. Kennedy is the only candidate who combines sound positions on most issues with polling numbers that suggest he can actually win the election.

At this writing (January of 2024), Kennedy has dramatically higher approval ratings than Biden, Trump, or any prospective duopoly (Democratic or Republican) nominees. In three-way election matchup polls against Trump and Biden, he is averaging around 18%. That’s people who say they’d vote for him; those who say they approve of him are over 50%. He is doing this despite his raspy voice, despite half the country not even knowing he’s running, and despite about half of those who do know he’s running only knowing the defamatory propaganda about him from the corporate “legacy” media. People who actually listen to the man predominantly come away impressed. This strongly suggests that he can dramatically improve on that 18%.

But how much does he need to improve, to get 270 electoral votes? What happens if he falls short of that? Is this a realistic project, or an exercise in wishful thinking?

I do not hold with those who don’t want to think about “what-ifs”. I come to this with the mentality of the engineer, not the motivational huckster. I know enough to take a hard look at a proposal and try to see if it’s feasible. I know it’s better to think in advance about what could go wrong than to find out the hard way.

I do not argue from authority or credentials. I do not ask you to take anything on faith. I do not want to waste my own time and energy, or yours, on a cause that has little chance of success.

I already knew, just from studying previous elections, that in a three-way presidential election, where the two popular vote losers run close, and all three candidates have nationwide rather than predominantly regional support, as a rule of thumb a candidate starts winning some states at around 20% of the national popular vote, and has at least an even chance at an electoral vote majority at around 37%.

But I wanted something a little more scientific, so I did a simple feasibility study. I will explain how I did it, so you can check my work, and do similar studies yourself. I used nothing but a pocket calculator, pen and paper, and 2020 election results by state, obtained online.

I would emphasize that this is not an elaborate simulation, and is not intended as a guide to where to put campaign resources. It is a simple, “back of an envelope” exercise to get a rough idea what a Kennedy victory might look like, state by state, to see if the picture that emerges that way looks believable or not.

Any such calculation necessarily involves assumptions. For a first try, I am assuming:

- The duopoly share of the vote splits the same as it did in 2020.

- The non-Kennedy, non-duopoly vote (Green, Libertarian, No Labels, et al, combined) is 2% of the total vote in each state. This is about what the national figure was in 2020. 2024 could easily see this get as high as 4%, if the Greens get ballot access in as many states as in 2016, and there is a No Labels candidacy. There is always some state-to-state variation, but I am assuming 2% for every state in the interest of simplicity.

- Also for simplicity, I am treating Maine and Nebraska the same as the other states, ignoring the fact that they assign some of their electoral votes based on plurality wins in congressional districts, and just using the overall popular vote percentages for those states.

Applying these assumptions, I use the following methodology:

- Find state-by-state 2020 presidential results online. Most sources will have the same vote totals and percentages. Make a list of the states, plus DC.

- For each state, calculate the duopoly winner’s share of the duopoly vote, expressed as a decimal. I will call this the lopsidedness index, L. This will be a little higher than the winner’s share of the total vote. The equation is L = W / (D + R), where W is the winner’s percentage of the total vote, and D and R are the percentages for the Democratic and Republican tickets. In all cases, L will be a number greater than .500 and less than 1.000. Enter the L value next to the state name or abbreviation on your list.

- Enter the number of 2024 electoral votes for each state on your list, next to the other entries. Note that these will be different than the 2020 values, due to reapportionment following the 2020 census.

- Try a hypothetical whole-number percentage for Kennedy, and see if it wins. To see if it wins, assuming 2% other non-duopoly, first subtract the trial Kennedy percentage from 98, which is 100 minus the 2. That’s the total duopoly percentage. Multiply that by L. That gives you the duopoly leader’s percentage, which is the number Kennedy has to beat. Is the trial Kennedy number higher or lower? If it’s lower, it’s not enough for a win; try a higher Kennedy number, and repeat. If it’s higher than the duopoly leader, it’s enough to win. If it wins by a point or more, try a lower one and see if that wins. You will quickly find the lowest whole-number percentage that will win that state, given the assumptions used. With this method, for 2024, the lowest percentage will be 33. Do this for each state and enter the result next to the state name or abbreviation in your list.

- Add up the electoral votes for the 33% states on your list. Is the number at least 270? If not, add the electoral votes for the 34% states, and see if that gets you to 270. If not, just keep going like this until you have at least 270.

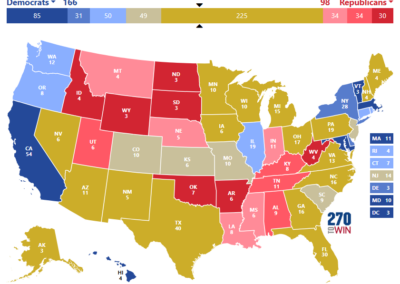

I found that I had to include up through the 36% states. With that set of states, I got 274 electoral votes, from 22 states. If Kennedy can get at least 36% in these states, he wins. There are 5 states where he only needs 33%.

- 33% states: AZ(11), GA(16), NC(16), PA(19), WI(10): 72

- 34% states: FL(30), MI(15), NH(4), NV(6), TX(40): 95 (+72 = 167)

- 35% states: AK(3), IA(6), ME(4), MN(10), NM(5), OH(17), VA(13): 58 (+167 = 225)

- 36% states: CO(10), KS(6), MO(10), NJ(14), SC(9): 49 (+225 = 274)

Electoral vote map, assuming duopoly popular vote distribution same as 2020, and 2% non-Kennedy, non-duopoly vote. Kennedy could win the gold states with 35% or less, beige states with 36%, lightest pink or blue states with 37%, medium pink or blue with 38%. Red and dark blue states would require over 38%.

Some readers will note that this method could easily be written as a spreadsheet. If you’re comfortable with that, by all means write one. You can then try all sorts of values.

I have just tried one other set at this writing. 2024 promises to be a year full of surprises, and at the best of times, in the words of Yogi Berra, “Predictions are hard to make, especially about the future.” We may very well see Biden, Trump, or both, NOT being the duopoly nominees.

However, we can get some idea how the race is shaping up by comparing those two candidates’ polling now with the numbers just before the 2020 election, and adjusting the actual 2020 numbers by the difference. Biden was polling about 54% in two-way matchups then. He’s polling about 49% now. Differences from 2020 will not be the same in all states, but, again trying to keep it simple, I took a look at how the numbers change if the Democratic ticket uniformly gets 5% less of the duopoly vote than in 2020. That would increase all the L values by .050 in all the 2020 red states, and decrease L by .050 in all the 2020 blue states where it was over .550. In the 2020 blue states that were under .550, the state flips to red, and the L value is then .500 plus .050 minus the previous amount over .500. For example, if the state was blue and L = .512 in 2020, it flips to L = .538, and the candidate to beat is now the Republican.

I also increased the hypothetical non-Kennedy, non-duopoly share to 4%. 2020’s 2% share is a bit low. 3% is about average. As mentioned earlier, 4% might actually be low, especially if No Labels fields a candidate.

Intuitively, we should expect that the 2020 blue states get easier for Kennedy to win, and the red states get harder. We should also expect that the higher other-non-duopoly percentage makes things easier, or at least makes the necessary percentages lower. But what is the net effect?

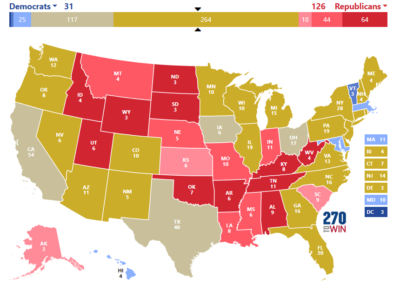

Running the exercise this way, the number of states needed increases from 22 to 23. However, Kennedy almost doesn’t need any 36% states. He gets 264 electoral votes with just the 35%-or-less states. He only needs any one of the 36% states. If we add all the 36% states, which include California and Texas, he has an electoral vote landslide (>2/3, or >359): 381 electoral votes! There is one state, Virginia, that he could almost win with 32% – but not quite.

- 33% states: CO(10), ME(4), MN(10), NH(4), NM(5), VA(13): 46

- 34% states: AZ(11), DE(3), GA(16), IL(19), MI(15), NJ(14), NV(6), OR(8), PA(19), WI(10): 121 (+46 = 167)

- 35% states: CT(7), FL(30), NC(16), NY(28), RI(4), WA(12): 97 (+167 = 264)

- 36% states: CA(54), IA(6), OH(17), TX(40): 117 (+264 = 381)

15 of the 22 35%-or-less states are in the previous set of 22 36%-or-less states. Ohio is also in that set.

Electoral vote map, assuming that the Democratic ticket gets five less percent of the duopoly popular vote than in 2020, and assuming a 4% non-Kennedy, non-duopoly vote. Colors mean the same as in the previous map. Kennedy could win the gold states with 35% or less, beige states with 36%, lightest pink or blue states with 37%, medium pink or blue with 38%. Red and dark blue states would require over 38%.

Not much blue on that map, is there? Just 5 points less of the duopoly popular vote did that. This illustrates the electoral college system’s tendency to amplify small changes in the popular vote margin of victory. Kennedy could lose any two of the four states with the most electoral votes (CA, TX, FL, NY), and still win the election, if he gets at least 36% in the other 24 in this set. If he wins CA or TX, he can afford to lose the other three biggest.

But what if Kennedy doesn’t get to 270, yet does carry enough states to prevent anybody from getting 270? What if he doesn’t carry any states, but peels votes disproportionately from one or the other duopoly party, sufficient to tip some individual states, and these are enough to tip the electoral vote? Both of these are quite possible, and they form a rational basis for duopoly adherents, or people merely resigned to duopoly rule, to shrink from voting for Kennedy once they get in the booth.

Taking the latter possibility first, there have been a number of recent polls that include a two-way matchup, and also a three-way with Kennedy included. These consistently fail to show a statistically significant effect when Kennedy is added. Both duopoly candidates get less, of course, but in some cases one does worse by a couple of points, and in other cases the other does worse by a couple of points. In some cases, there’s no effect at all. Two points is not a statistically significant change, especially when even the direction is inconsistent.

However, there is some chance this could change a bit as Kennedy gets better known, although we don’t know how much, or in which direction.

What if nobody gets 270 electoral votes?

First of all, this is less likely than people tend to think, because of the electoral college system’s tendency to amplify small margins of victory. Of the 59 presidential elections so far, there have been 10 where more than two tickets carried states. Only one of those went to the House, and in that one, four tickets carried states. Nevertheless, it is possible for this to happen in a three-way race.

If nobody gets 270 electoral votes, the House of Representatives chooses the next president. This occurs after the House is sworn in, so it’s the representatives just elected who are voting.

When the House votes on this, they don’t do it in the usual manner, with each representative having one vote. Instead, each state has one vote, and the entire state delegation have to settle among themselves how to cast that vote. The Constitution does not say how they are to make that decision, and it does not say whether a majority of those 50 votes is required, or just a plurality. It only says they have to choose among the top three electoral vote getters. However, it is probable that the state delegations will decide internally by plurality vote, and it is probable that most of the representatives will vote by party. This would result in a Republican win, even if the Democrats narrowly retake a House majority, because a lot of those Democrats would be from large-population states that only have one vote, just like all the others.

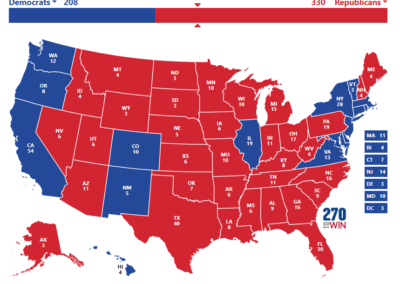

For the Kennedy candidacy to change the outcome of the election by sending it to the House, it has to be an election the Democratic ticket would otherwise win. For that to be so, the Democratic ticket’s performance in November has to be quite a lot better than Biden’s polling in January. The trend at this writing appears to be the opposite way, while Kennedy’s numbers are improving.

Electoral vote map, using same assumptions as the last one, except no Kennedy candidacy.

Then again, Kennedy has farther to go. But he’s got nine months.

In 1998, Jesse Ventura demonstrated, as the Reform Party candidate in the Minnesota gubernatorial election, how an outsider candidate’s numbers can improve over the course of a campaign. Before the televised debates, Ventura was polling at 9%. People who didn’t know him tended to assume he was just some knucklehead wrestler. Then they heard him speak. He won the election with a 37% plurality. A similar dynamic applies with Kennedy.

It is quite likely that there will be no televised presidential debates in 2024, provided Kennedy gets on the ballots. The duopoly parties know he’d clean their clocks, no matter which of their prospective nominees they choose. In all likelihood, they will rely on the corporate media to try to keep Kennedy unheard, defamed, and marginalized.

But now we have the internet.

It is going to be an interesting year.